China's Mao-Deng development model

Otto Kolbl

The Chinese combination of Maoism focused on social development followed by a very slow and gradual liberalization under Deng Xiaoping turns out to be an extremely efficient development model. Unfortunately, for mainly ideological reasons, Mao's and Deng's policies are generally considered to be in conflict with each other. Only a comparative approach with other developing countries based on consistent long-term statistics provided by international organizations can allow us to understand the positive interaction between these two approaches to development.

The discussion about China's recent development under the Communist Party of China (CPC) is often reduced to the question whether Maoism was the right approach or whether Mao's policies were a disaster and Deng Xiaoping put China on the right track. This discussion is extremely polarized, to say the least. Among the Western academic world and media, there is virtually only one opinion: whoever does not consider Mao a bloody dictator and a disaster for China is unable to think freely and has been brainwashed by communist propaganda. Actually, a comparative study of long-term statistics shows a completely different picture: The combination of Maoism with Deng's reforms has allowed China to develop faster than any other country in the world. This is true not only for economic development, but also for social development like the reduction of mortality and the spreading of literacy.

The needs and aspirations of the people should always be put in the center of any discussion of development. Photo Otto Kölbl, Siping (Jilin province, China), 2012.

This might sound quite surprising, especially if we consider the obvious differences in development level between mainland China and Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore etc. However, a look at the long-term development of these countries and regions shows that the differences are not due to the speed of development, but to the time in the past when they started their development process.

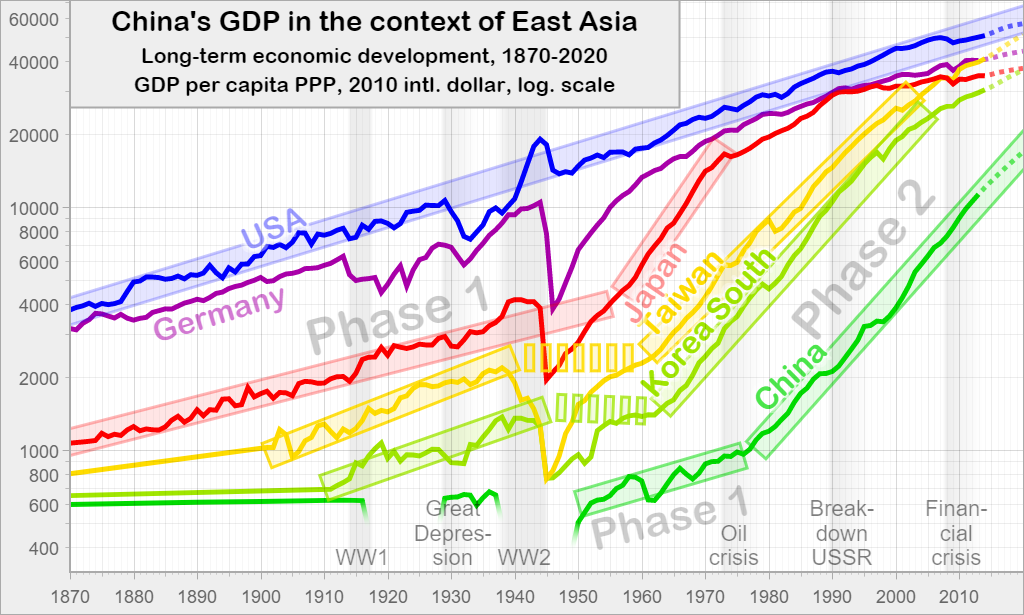

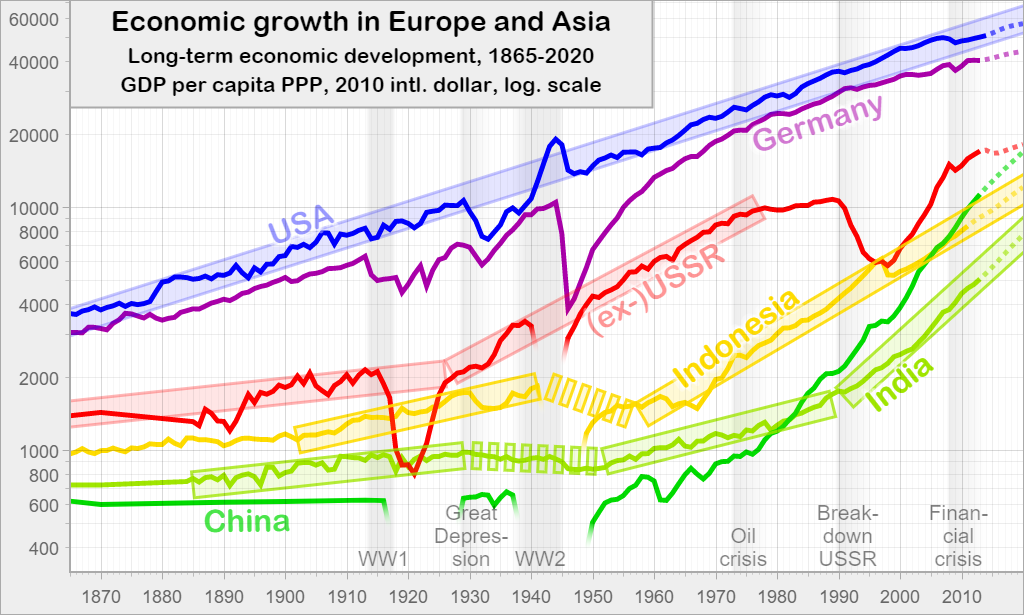

The two charts below shows clearly that almost all countries in Asia and Chinese regions under foreign control like Hong Kong and Taiwan have started developing between roughly 1850 and 1900. On the other hand, nation-wide statistics show absolutely no development in mainland China. These charts are based on per capita GDP compensated for purchase power parity, which is considered to be the best indicator of the standard of living and the level of development. Actually, statistics before 1950 are often disputed and the chart below integrates data from various sources, some of which contradict each other. However, experts agree on the general picture; for example on the fact that in China in the first half of the 20th century, major cities experienced some development, but most of the countryside even saw a deterioration of living conditions.

The first question which we should ask ourselves is therefore why mainland China is almost the only Asian region which saw no development before the coming to power of the CPC in 1949. The Opium Wars have certainly played a role in this; the disastrous consequences on the Chinese society of this shameful episode of European colonial history are often misrepresented by Western authors. On the other hand, all regions in Asia have had their fair share of colonial aggression, in many cases an even more destructive colonization than what took place in China. The conclusion of my research is that the highly cultivated Chinese elite, partly under Western ideological influence, had lost any sense of responsibility. They had become so totally self-serving and corrupt since roughly 1800 that they were totally unable to lead China through a development process worth its name. This also explains why opium trade became a terrible social disaster in China, whereas the elites of other countries have been able to defend themselves and the whole society against this terrible poison to which they were equally exposed.

Poppies and terraced rice-fields, by Mrs. Archibald Little, Sichuan province (China), before 1899. As this picture and many more show, only part of the opium which devastated China's society before 1949 was imported by British trading companies; most of it was home-grown. Find Mrs. Archibald Little's amazing book "Intimate China" for free on www.archive.org and www.gutenberg.org.

The charts above and below also show that among all Asian countries and regions which have experienced a period of fast economic growth, not even one has been able to do so starting from a poor agrarian economy, which all of them had until at least 1850. All of them have gone through a period of slow growth of several decades, sometimes lasting around 50 years, sometimes lasting one century or more ("phase I" in the chart above). Only after this first phase dedicated to the buildup of infrastructure, education, healthcare and some industrialization, they could enjoy a period of fast growth ("phase II"). This is true both for countries which are now more advanced than mainland China and for those which have started moderate or fast growth after China. The following chart shows the growth curves of several other Asian countries and of the (former) USSR, i.e. all its successor states taken together after 1990.

Mao's contribution to the development model

China is the only country in the world which has achieved fast development after only 27 years of slow growth under Mao Zedong (1949-1976). The second fundamental question is therefore: what makes development under Mao Zedong so efficient that he has been able to build up the basis for fast economic growth twice as fast as any other country in the world? The achievement of the CPC becomes all the more impressive when we realize that it turned the least well performing country of the region ("China, the sick man of Asia") into the best performing one.

The skyline of Dalian (Liaoning province, China). Photo Otto Kölbl, 2012.

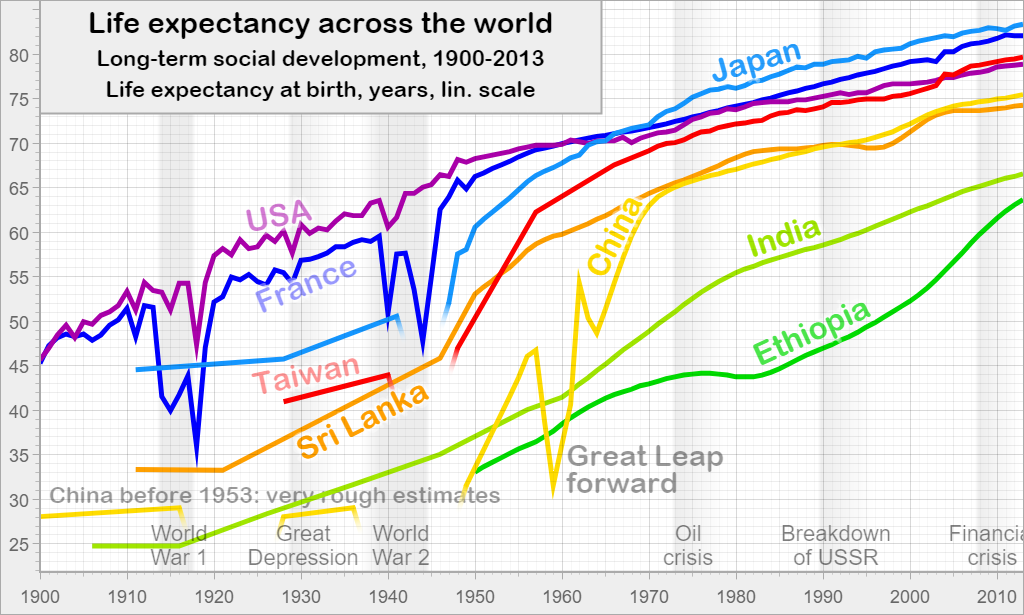

Historical research and statistics reveal that this was made possible by Mao's policy of mobilizing the huge workforce of the countryside through collectivization and mass mobilization campaigns. In an extremely poor country like China at that time, this was probably the only way to achieve in such a short time the improvement of infrastructure, and education and healthcare to the level which is necessary for fast economic growth. Statistics provided by international organizations like the World Bank and Western academics show that Mao's social policies have saved hundreds of millions of lives, whereas the late Qing dynasty (until 1911) and the Nationalist party (1912-1949) did nothing to improve the living conditions of the huge majority of the population. The following chart gives us a good overview of both social progress and Mao's most disastrous error, namely the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962), in comparison with other East Asian countries:

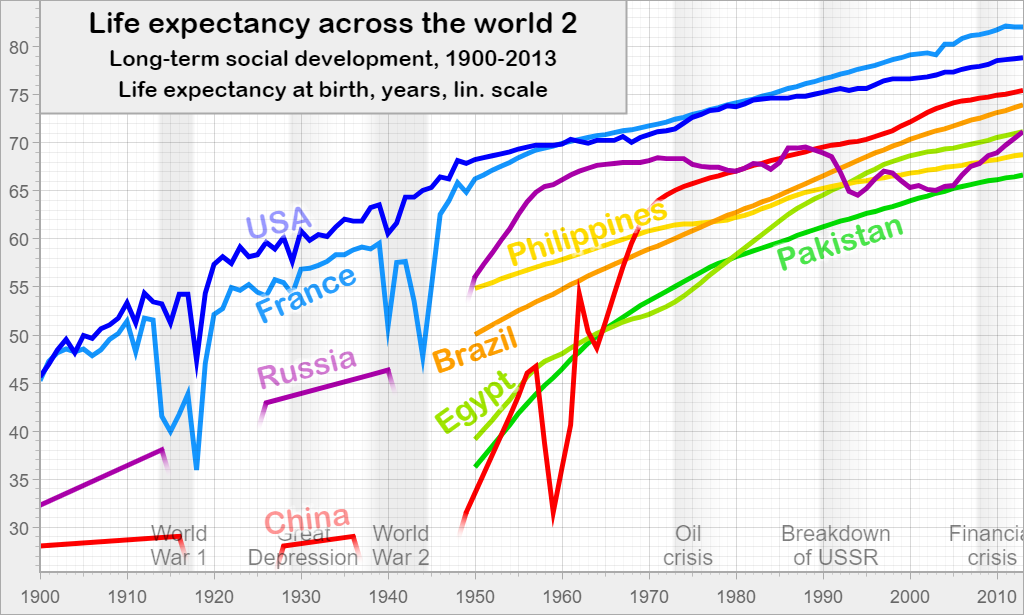

Life expectancy in China before World War 2 is a hotly disputed topic; there are many conflicting estimates. Figures for Japan and its colony Taiwan as well as for India, Russia and Western countries are much more precise. From 1950 on, reliable estimates are available for most countries. For China from 1953 to 1963, I use the data provided by an expert from the World Bank because official statistics are inadequate. However, the global picture is quite clear: from a social situation far worse than in almost any other country, life expectancy in China has made huge progress under Mao Zedong; actually, the improvement during his 27 years in power is unique in the whole world. The following chart allows comparisons with more countries across the world:

Not only among the East Asian countries which enjoy now a high standard of living, but also among South American and even African countries, it is very difficult to find some where the situation was as bad as in China just before the CPC came to power in 1949.

With regards to infant mortality, we get a similar picture as with life expectancy. Solid data is available about social progress under Mao Zedong, but the academics who pretend to inform us about this important period in Chinese history have decided to ignore it. Actually, they don't ignore it entirely, they just pick the pieces which fit into their discourse. For example, with regards to life expectancy, they take only the Great Leap Forward and calculate the deaths. Disasters must be remembered, this is absolutely necessary to prevent something similar from happening again. But will these academics tell us that even in the worst year of this disaster, life expectancy did not go below values which were perfectly normal until ten years before, under the late Qing dynasty or the Nationalist Party? Or that within less than 20 years after the CCP came to power, life expectancy had doubled from probably around 30 years or less to more than 60 years? Has anybody even tried to calculate the number of lives saved, as compared to a hypothetical continued rule by the Nationalist Party which has never cared about social progress in the countryside?

Surgery with acupuncture in the Shandong Provincial People's Hospital (Jinan), China. Photo William A. Joseph, 1972.

Of course, this does not mean that China under Mao Zedong was a paradise for farmers. In order to push development further than what could be achieved through improvement of agriculture, Mao extracted as much capital as he possibly could from the population to finance industrialization. Even though living conditions improved a lot during this era, the huge majority of the people were still extremely poor when the reforms set in at the end of the 1970s.

We should also consider that development cannot be reduced to its socio-economic aspects alone. Progress in the field of social and economic rights was achieved using often brutal repression against the former privileged elite, political opponents within and outside the Communist Party and many, many innocent people. As a whole, there was extremely little individual freedom under Mao Zedong. The Chinese state during that era was a perfect example of a totalitarian state. Not only public life, but even many aspects of private life were controlled directly by the state or by the local communities according to official guidelines. The whole society was organized into communes, brigades and work teams; even for travelling outside of your commune, you needed a travel permit.

A work team in Shashiyu, Hebei province, working on terracing the fields. Even today, if you ask farmers when the agricultural infrastructure they use was built, you often get the answer: "In the 1970s". Photo William A. Joseph, 1972.

Beyond these institutionalized forms of control, Mao relied on the mobilization of local communities to enforce his policies. The community-managed land distribution in the early years and the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution in the ten last years of Maoism are examples of these less organized forms of violence. If we consider that all this happened without much oversight by the authorities, it becomes obvious that this violence was also directed against many innocent victims.

During the Cultural Revolution, the Red Guards attacked not only corrupt government officials and members of the traditional elite who wanted to get their privileges back. Many people who worked hard to develop China, but had the "wrong" class background or refused to give up their religious beliefs, were the targets of brutal forms of humiliation and violence. Photos 1 and 2: photographer unknown, provided by Thomas H. Hahn. Photo 3: photographer unknown.

This must be seen in the context of a country which before 1949 could reasonably be compared with present-day countries like Afghanistan and Somalia. China (1916-1928), Afghanistan (1989-1998) and Somalia (1991-2012) have all gone through a phase of failed state, where institutions broke down completely and warlords competed for power. Between 1850 and 1949, China had known only 46 years of peace between 1870 and 1916, shortly interrupted by the Boxer Rebellion 1899-1901 and the overthrow of the monarchy in 1911. The nine years between 1928 and 1937 were also relatively peaceful in major parts of the country. Otherwise, almost half of that century was made of a succession of wars, civil wars, insurrections and warlordism. Before 1949, the Chinese society, especially in the countryside, was totally wrecked by lawlessness and widespread opium addiction, in particular among the ruling elite, and structured more by local tyrants and organized crime than by a functional administration.

Under the Qing dynasty and under the Nationalist Party, opium smoking was much more widespread among the high society than among the population in general. Photo Lai Afong, ca. 1880.

Within the last one and a half centuries, only very few countries in the world have gone through such a long period of endless disasters. It is quite reasonable to assume that each single Chinese has tried to find a solution. Some of them have come pretty close to restoring order, only to see the country relapse into chaos again after a few years or decades of relative stability, but no development. The CPC must definitely be credited with not only restoring order, but also initiating the fastest socio-economic development process the world has ever seen. Just look at the total failures of Western recipes applied to failed states like Somalia, Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, and you will better appreciate what this party has achieved.

We can certainly learn a lot by analyzing Mao's era, but such research must be based on comprehensive data about all the different aspects of human life. Reliable statistics produced or verified by international organizations or independent academics is easily available, but Western academics working on Mao Zedong seem to agree on ignoring the available data on social progress. If they mention some of it, they tend to consider that one sentence is enough, and they hardly ever provide comparative figures about the development of other countries. Nobody seems to care about the fact that these statistics tell us about human beings who were saved or who died, often under terrible circumstances. Instead, only the deaths resulting from policy errors or repression are counted and the final conclusion is always the same: Mao was one of the worst dictators of the last century.

In China, there is much more diversity in the discussion about Mao Zedong, but it is generally only based on official Chinese statistics. This means that the debate turns into a question of trust into the National Bureau of Statistics of China, which makes any kind of agreement between pro-Mao and anti-Mao extremely unlikely. Both in China and the West, academics must learn to overcome ideological preconceptions. This means among other things that they should invest as much time and effort into looking for data which goes against their personal preferences as for data which confirms them.

"Helping mum to learn how to read and write". The Mao era saw huge progress in education. Schools were set up not only for children; adult schooling was also considered a priority. On the other hand, the picture for higher education is mixed at best. Photos: China Posters (left), William A. Joseph, 1972 (right).

The importance of this question goes well beyond a simple academic debate. Among other things, it is an important factor in inter-generational communication in China. In many families, heated debates take place between on one side the grand-parents who still remember life under Mao Zedong and sometimes even before, and many of them tend to praise his achievements. On the other side, many of the middle and younger generations tend to consider Mao's management of economic development a disaster for China; they will reply to the older generations that they have been brainwashed by Mao's propaganda and are unable to have a clear judgment about this topic. In my discussions with Chinese people of all ages, I have always made the experience that using data from a great variety sources, e.g. from Chinese and also international sources, can often bring people with different opinions to agree at least on some issues. The research method proposed here can therefore contribute to a better mutual understanding not only between China and the West, but also within the Chinese society and families.

Reforms and opening up under Deng Xiaoping and his successors

The way in which Deng Xiaoping and his successors have built on Mao's legacy to achieve fast economic growth and huge improvement of living conditions is also unequaled in the world: no other country has been able to achieve fast growth starting from such a low level of development.

The Flying Eagle Boat Company, here during the inauguration of a new production site, was founded in the 1980s. It quickly became one of the world's leading producers of competition rowing boats. Photo Otto Kölbl, Zhejiang province (China), 2003.

Other countries like the Soviet Union have also used collectivization and planned economy for the initial phase of development, but the transition to fast growth did not always go well. The second chart above shows in an impressive way how the countries of the former USSR saw their economies break down completely when liberal reforms were introduced in the 1990s.

If we consider that a good infrastructure, education, healthcare and some industrialization are the necessary basis for fast economic growth, it is quite obvious that the Soviet Union met the conditions for a huge economic boom long before 1990. Whereas in China, Maoism was replaced by Deng's reforms after 27 years, the Soviet bloc remained stuck in planned economy for more than 70 years. The fast growth potential which was built up never became reality; this discredited in Communist Party in the eyes of the population. When the Soviet bloc started reforms in 1990, China had already shown the path with more than one decade of fast economic growth. Unfortunately, both the leaders of the former Soviet Union and their Western advisors were too arrogant to even consider the possibility of learning from China.

So, which were the lessons Soviet leaders could have learned from China? It seems that Deng's recipe did not simply consist in "economic liberalization", as it is often explained, but in an extremely slow liberalization, drawn out over predictably 50+ years. Still now, more than 35 years after the beginning of the reforms, additional sectors of the economy are progressively liberalized.

Other aspects of the Chinese system are much more difficult to grasp. Most Western authors like to depict the Chinese Communist Party as controlling every small detail of life and business; reality is of course much more complex. Some key sectors of the Chinese economy like (legal) banking, energy, telecommunications etc. are totally controlled by the state. On the other hand, when talking with entrepreneurs, especially with owners of small family businesses, I am often surprised to see how little the state interfered with their business activities. As compared to other countries, administrative paperwork is reduced to the minimum; rules and regulations are quite vague and often applied in a creative way. Only when the Party considers that there is a serious problem, it intervenes; the vague regulations do not really restrict its ability to do so.

Unlike Western consumer electronics retailers, the Zhongguancun consumer electronics market in Beijing is made of a myriad of small family enterprises. Photo Otto Kölbl, Beijing (China), 2012.

Obviously, this system facilitates the creation of new companies; on the other hand, it offers few safeguards against abuses, for example by business partners. What might sound like a disaster for economic development is actually one of the secrets of China's development: this relatively insecure business environment favors the emergence of small family businesses which operate within closed local business communities. Because business partners know each other, transaction costs are extremely low. The absence of complex paperwork allows even farmers with little formal education to set up businesses. The formal complexity of the "rule of law" would drive them out of business and allow huge national or multinational companies to take over the market, as they do it in Western countries.

The Moslem Hui minority, recognizable here with the mosque in the foreground and their yellow and green houses, is a good example of a tightly knit community which has done very well in business. Photo Otto Kölbl, Taktsang Lhamo/Langmusi (Gansu province, China), 2012.

These are only two among many factors which have made the success of the reforms starting in 1978, but are poorly understood by both Western and Chinese scholars who tend to focus on prestigious high-tech companies and international exchanges.

To sum it up, the Chinese Mao-Deng model of development provides many innovative solutions for poor countries. The development and implementation of these solutions by the Communist Party have allowed China to develop faster than any other country in the world, both from the economic and the social point of view. On the other hand, the development models of many other Asian countries and regions cannot be applied to present-day poor countries, because they were driven by militarism (Japan), because they were determined to a large extent by foreign rule and support (South Korea and Taiwan) or because they relied on the parasitic exploitation of neighboring production bases (Hong Kong and Singapore).

It is about time for an analysis of the Chinese development model based on reliable data, in comparison with the development of other countries and regions in Asia and across the world. This is the only way to evaluate the performance of various development models. International organizations and various Western specialists in socio-economic development provide a huge wealth of data for all the countries in the world. This data has been collected or calculated using the same methodology for each country and is therefore free of ideological bias.

The same is seldom true when we consider how Western China experts use this data. Virtually all of them keep repeating that the Mao era with its policies of isolation and collectivization were a total disaster and that Deng Xiaoping could have done much better if he had opened up China more to foreign influence and liberalized the economy faster. Sinologists and Western media have always loved to describe the Chinese communist regime as totally absurd in its functioning, irrational and inhumane. How can such a description be upheld when we look at the data provided here which is widely considered as being reliable? How is it that China under Chiang Kaishek was unable to provide any improvement in living conditions to the Chinese people when the most advanced Western powers competed in providing development aid? After 1949, how could an absurd, irrational and inhumane regime achieve not only economic development, but also social progress faster than any other country in the world? It is disappointing that Western China experts do not look at the data used here, even though it is easily available; one reason might be that it is difficult for them to accept that China did much better without their "help" than with their help.

Missionaries took not only many pictures of pre-Mao China like this one of an operation in Changde (Hunan province, China), ca. 1900-1919; they have also contributed to improving healthcare and education. It might seem a paradox that the huge majority of the Chinese had to wait for Mao to come to power and expel all the missionaries in order to be able to benefit from social progress. Source: International Mission Photography Archive on Wikimedia Commons.

It is much more difficult to understand why Chinese researchers have never realized that data provided by international organizations and highly regarded Western experts allows us to understand the Chinese model of development much better than the exclusive use of Chinese official statistics. Few of them have ever travelled to other developing countries to see for themselves what the result of other development models looks like on the ground. The lack of such a comparative approach to development is certainly one of the reasons why the Chinese development process is so poorly understood outside of China. This leaves unchallenged those who carefully pick the data which seems to support their criticism of past and present Chinese policies.

Conducting rigorous research about the Chinese Mao-Deng model of development using a comparative approach will not only improve mutual understanding between China and the rest of the world; it will also provide precious data for countries which are still looking for an adequate model to improve the living conditions of their people. Conversely, such an approach can also provide new ideas for developing areas of China which have not yet been able to benefit from the economic boom of the coastal areas.

Swiss mountain tourism and Latin American adventure tourism can certainly contribute to the development of China's western regions. Photo Otto Kölbl, Zermatt (Switzerland) 2014; Coroico (Bolivia) 2011.